Carbon markets, bad to the bone?

Carbon markets are at a crossroads. At scale they have been around for almost a decade. During that time they have seen bad press, scandals, fraud, carbon prices dropping to €0, and they have never been less than controversial.

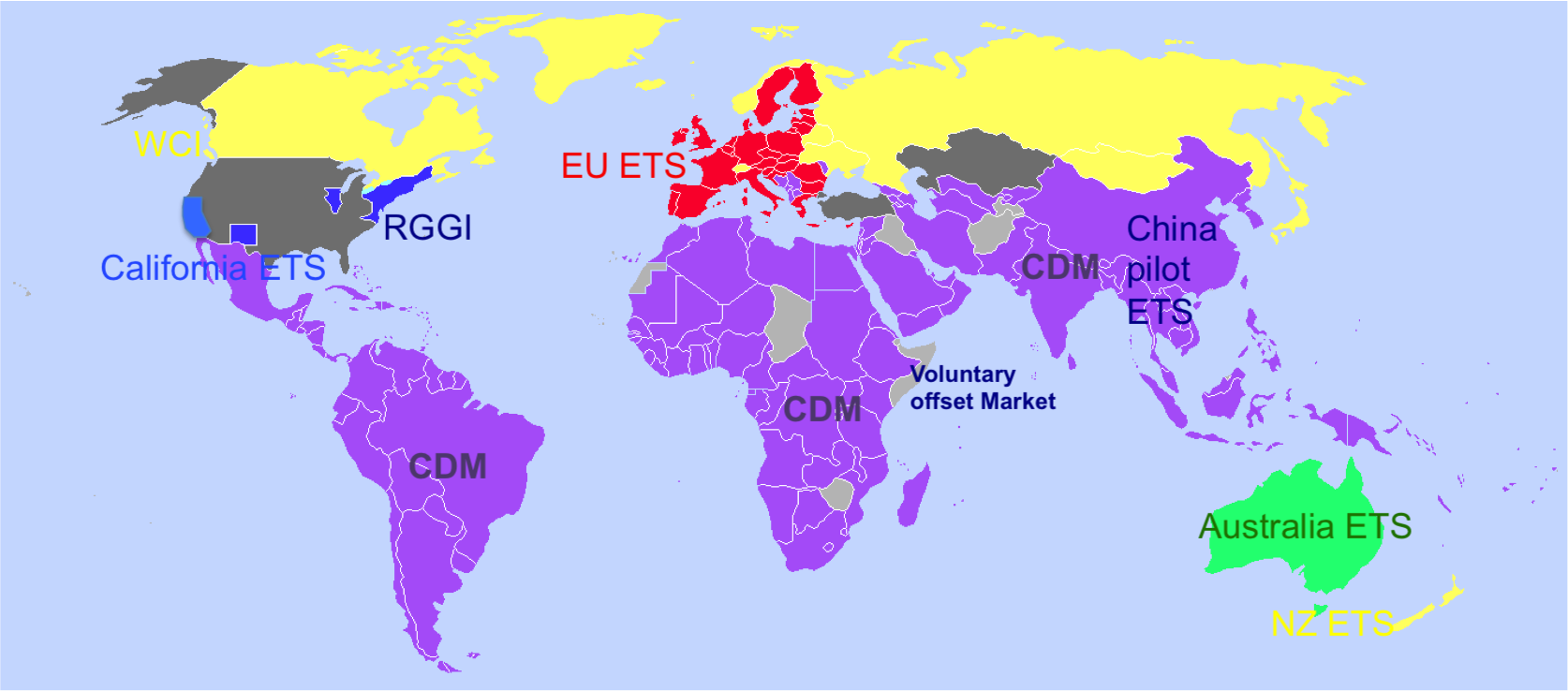

Many concerns are justified. However, most people, including the press that reports about it, do not really know how carbon credits are created, or what is meant with the term carbon market. To judge, one needs to understand the topic. And that’s not easy. There are different systems that cover varying segments of the economy and may or may not be linked or related to each other. As such certain concerns deal with specific markets and are not an issue in other markets, etcetera. Media attention and criticism has been directed mostly at three distinct systems (there are others), emissions trading schemes and the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) in the regulated market, and the unregulated Voluntary Carbon Market. Let´s discuss some of the criticism, and then judge for yourself.

Carbon markets are based on “hot air”

Initially when the countries that signed up to the Kyoto Protocol negotiated targets, it resulted in many Eastern European countries (namely Russia) receiving billions of tons of free allowances which they could sell on the market. Reduction targets were based on country-driven emissions forecasts and 1990 was chosen as reference year. Most of these countries had experienced an economic collapse shortly after the fall of the Berlin Wall and before the negotiations of targets (1997), drastically reducing industrial and energy output. The countries were expected to rapidly recover economically, so that targets would be justified, however this did not happen. Most Western European countries however declined to buy this “hot air” from Russia and rather focused on carbon credits from the CDM besides engaging with domestic abatement efforts. Russia has now bailed out of the 2nd commitment period of the Kyoto Protocol, where they may not have received these free allowances. Politicians can not afford to make this mistake again. This can be avoided in any future agreement (possibly by 2015) by choosing sensible base years not only for Russia, Ukraine and Poland, but also countries such as the USA, China, India and Brazil that are likely to join in this time. Any surplus allowance from previous commitment periods should really be cancelled out if we want to seriously achieve climate goals.

More hot air..

In the European Emissions Trading Scheme, a cap-and-trade scheme for Europe´s largest carbon emitters, the first phase (2005-2007) saw carbon prices drop to zero when the market turned out to be oversupplied with allowances to emit. The phase ended up over allocated because allocations were not based on real data but estimated historic emissions and growth figures. The European Commission had to rectify this in Phase II (2008-2012) by setting a tighter cap. However, the reduction mostly affected the power sector while industry on average ended up receiving more than they needed (hot air). This effect was partially caused by a decrease in production following the economic crisis, and probably partly to protect the competitiveness of Europe´s industry. Meanwhile the power sector destined to make the real cuts was able to pass on the cost of carbon to consumers. The Commission has again set a stricter overall cap for phase III, which started this year, although the economic crisis might still have an influence.

Most governments that implement cap-and-trade schemes will gradually increase the stringency phase by phase to protect participants from competitive disadvantages with respect to international trade. The EU ETS, as a first of its kind, has mostly learned by doing. Hopefully the succeeding domestic schemes, many or are planned or have recently started around the world including the state of California, Australia, China, and South Korea, will take note and do it right from the start.

Even more hot air…

The Clean Development Mechanism and the Voluntary Carbon Market have had a rough ride over the last decade as well. Cases have been cited where projects were non-existent or projects not additional, i.e. would have happened anyway without the revenues of the carbon credits. Additionality is a requirement under the UNFCCC as well as for most established voluntary carbon standards. The former citations stem from the early days of the voluntary market when there were no project registries, third-party certifications nor Standards. We can safely say that such reportings are confined to history as the voluntary market has evolved.

Additionality of projects however has been a problem and is an arbitrary exercise as it is. It is for instance rather difficult to prove that a project of wind turbines would not have been economic without the revenues of carbon credits, considering the rather small share of income from carbon credits compared to the electricity revenues, compared to other technologies. The UNFCCC has made amendments to- and is still reforming the CDM rules and requirements to deal with these concerns. Media attention focusing on malicious practises has increased scrutiny on projects. Several third-party verifiers have been suspended for not adhering to the rules. However, ensuring additionality is subject to a slow bureaucratic process which in turn receives much criticism because of the associated costs and limited turn-over of emissions reductions (as a project will not receive start-up capital and thus create emissions reductions until it is approved).

Companies make millions from these systems

The steel and cement sectors participating in the EU ETS have seen the biggest surpluses of allowances between 2008 and 2010. During this period, ArcelorMittal, one of the most energy-intensive companies in the world, may have made over €1.4 billion as a result of its obligations under the EU ETS. This is equivalent to over 16% of its net income over these three years. In 2010, the value of the surplus was equal to 19% of Lafarge´s (cement), 21% of ArcelorMittal´s (steel), and almost 30% of Heidelberg Cement´s net income (using the 2010 weighted-average EUA carbon price of €14.64/tCO2). Companies in these sectors relate their surplus to the decreased production during the economic crisis. Other companies however were short, i.e. had to buy allowances on the market, or reduce in-house.

So yes, there are companies who have financially benefitted from carbon markets possibly without even having invested a penny in low-carbon technologies. That means that they either did not have stringent enough targets, or that they reduced production (which has abundantly happened during the financial crisis), or a combination of both.

Carbon markets are an excuse to emit more

From the point of view of compliance markets, as explained in the beginning, the principle of a cap-and-trade scheme is that on the whole emissions are reduced down to a certain target. It does not matter how that target is achieved, i.e. companies are free to buy allowances either from their peers, or from cheaper emissions reductions from developing countries (CDM). However, in order to achieve the target in theory there should always be companies that invest in- and implement abatement measures in-house (if the targets are adequate). And the less companies would reduce emissions in-house, the higher the carbon price would become making in-house abatement more economic than buying on the market. So yes, there could be companies who increase production and choose to keep using dirty technologies, but if the targets are stringent enough that does not matter from an environmental point of view. And it will not make sense to do so from an economic point of view if prices go up to €100 per tonne CO2 in 2050, which could happen even though it seems a long way off now at current prices of around €3-4/tCO2 in the EU ETS, and well under €1/tCO2 for the CDM.

Fraude and theft

In addition there have been cases of fraud and theft in the EU ETS and fraud in the CDM. Here I can be short, there has been fraud and theft in any private and public sector throughout history so why would that not happen in the carbon markets? It seems to be inherent to humanity, not carbon markets specifically. This is plainly a matter of increasing enforcement measures, which has happened.

Dirty technologies earn carbon credits

In theory all approved technologies under the CDM should reduce (or perhaps rather offset) carbon emissions, unless fraud is committed. However there are controversial technologies that are claimed to have detrimental socio-environmental effects.

The UNFCCC has so far been receptive to criticism and has made reforms and amendments to the rules, phasing out controversial technologies or applying strict rules to prevent detrimental effects. Certain technologies have so far not been approved by the UNFCCC because of these kind of doubts. Biofuel production potentially conflicts with food crops and has sparked controversy especially regarding the (continuous) cutting of rainforest for palm oil exploitation in Malaysia and Indonesia. It has been a hot topic for years and no methodology (except for one limited to biofuel derived from waste biomass) so far has convinced the regulator.

These type of projects make carbon markets controversial, especially when they receive media attention. However, they are only a fragment of the technologies that are being used, and they should not blur the fact that the CDM is mostly about clean technology and renewable energy.

Emissions are not being reduced

To discuss this, we need to run through the various carbon market systems at different political levels. The hot air issues discussed before are a clear example that emissions are overall not being reduced on national level in countries such as Russia, the Ukraine and Poland. On sectoral level, the EU ETS, the largest carbon market in financial terms, is not doing much better apart from the power sector, whether this can be accredited to the allocations or decreased production due to the financial crisis.

The Voluntary Carbon Market does reduce emissions but currently only on a small (yet growing) scale compared to the overall size of the carbon markets. The CDM is seen as a zero-sum game, i.e. is meant as an offsetting mechanism. Because of additionality issues discussed previously some argue that the CDM thus rather increases emissions, as those projects would have happened anyway yet deliver carbon credits to companies and governments that in turn can emit more. The same can happen when baselines for CDM projects (i.e. the emissions that would occur without the project) are overstated.

That is one gloomy picture wouldn´t you say?

So how bad are they?

All new markets have start-up problems. The issue is will the designated authorities deal with these problems adequately? I will argue that in the current world we live in, the basic concept of carbon markets is not the problem, it just needs to be gradually perfected.

Whether we like it or not, we are living in a capitalist world, and carbon markets are a part of that. The capitalist system has come under fire over the last few years, especially through banks who also have an important part to play in carbon markets. But as long as we do not desire or set about a global revolution we need to be pragmatic. Even if we wanted to, we do not have the time for radical political changes, we have to act now. So if some companies make money off carbon markets but the end goal of stopping global warming is achieved then why should we complain? We need to stimulate companies in doing the right thing, and that means giving them potential financial or strategic incentives as they need to answer to their shareholders. Carbon markets could be your best bet to engage corporates in the climate change battle.

Most of the problems associated with carbon markets that have been discussed in this article are implementational issues that can be improved. A major condition is political will. In general it is difficult for people to think long-term, even more so for politicians who have perverse incentives to think short-term. A new international climate change agreement for 2020, after two Kyoto commitment periods, will need to show ambition, and not hot air. All major emitters, including the USA, China, the EU, Russia and India, have now indicated they are willing to take on targets from 2020, a major step. Before 2015 we will know how serious they are about this. It is however always a game of compromise, this is why Russia and the eastern European countries got their hot air, and next in line may be the developing countries that have not had the chance to “grow”. I am moderately positive that if we would have time, eventually we would get there. But we don´t have the time.

In cascading targets down to their economic sectors, governments will need to get tougher on their industries if we want to save the planet in time. We may be too late already. On the whole the EU is taking a leadership role, even if the pace is too slow and eight years of EU ETS have not been enough to properly engage industry. And the US and China still have to follow suit. Additionality in the CDM is an issue, but cap-and-trade schemes are limiting the amount of CDM credits that can be imported, and the UNFCCC is putting significant efforts in to ensure integrity. If anything the CDM is preparing developing countries to take on targets of their own.

Carbon markets are merely a non-exclusive tool on our way to a low carbon world. More solutions are needed, but it’s a matter of “and”, rather than “or”. Ideally, from a save our planet point of view, a global carbon market would be created with sectoral targets for all countries thus eliminating competitiveness issues, providing clarity, continuity and a global carbon price for private investment, and enabling governments to be ambitious. Sadly there are probably too many political and economical discrepancies for that scenario. If however we establish a global climate treaty involving all countries such as is planned for 2015, and we keep on expanding, strengthening and linking up the patchwork of local and regional carbon markets and other carbon pricing mechanisms out there we may sufficiently boost low carbon development and domestic action.

One more crucial issue. Carbon markets are currently designed to allow for growth. The concept of growth is debateable and controversial, yet inherent to the capitalist system. The financial crisis has been good for the climate change battle, as we established contraction and we have reduced emissions around the globe by simply switching off machines. Long live the financial crisis. In the climate debate and negotiations, developing countries demand to be allowed to grow economically which seems fair enough as they have to deal with poverty alleviation and have not had the same chances as the industrial countries. However growth still is a holy word for the developed world as well, and the buzz words now are “green growth” or sustainable growth”. We have to however seriously ask ourselves if continuous growth is compatible with the goal of a low carbon society. Probably not. Before we find the answer to that question let´s continue with, criticise and optimise the carbon markets. Its either that or sustaining the financial crisis.

***

An adapted version of this blog was posted on the Climate & Development Knowledge Network website (read it here) in July 2013.

Full versions including background information on carbon markets were published on:

Swapsee in July 2013 as “Carbon markets, bad to the bone?”,

and in 2050magazine in August 2012 as “Carbon Markets: Are they really bad to the bone?”; 2050magazine issue 3; p52-66; August 2012; (http://www.2050publications.com).

Howdy, There’s no doubt that your web site might be having internet browser compatibility issues. Whenever I take a look at your blog in Safari, it looks fine but when opening in IE, it’s got some overlapping issues.

I just wanted to give you a quick heads up! Aside from that, wonderful blog!

Thank you! much appreciated!

Max